Before you can learn how to trim a hoof, you need to understand some basic things:

1)The anatomy and parts of a hoof

2) What a normal and abnormal hoof looks like

3) How to recognize planes and flat surfaces versus angled ones

4) What tools to use and how to use them

5) The basic steps of trimming

This series is a compilation of many images to help bring a lot of information to one place, for those who want to learn more about hooves without spending hours searching on the internet.

Part One:

Anatomy and parts of a hoof:

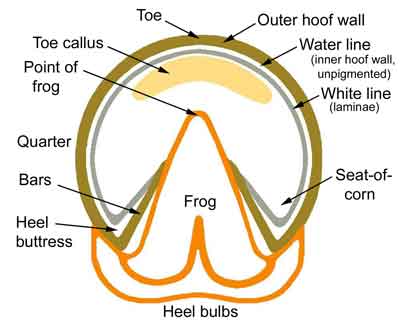

This chart is a good place to start.

Most people know what the outer hoof wall is. It consists of two parts, the outer and inner. The inner hoof wall does not have pigment – it is white. This is also called the “water line.”

This is often confused with the “white line” because someone was not thinking clearly when they named the hoof parts.

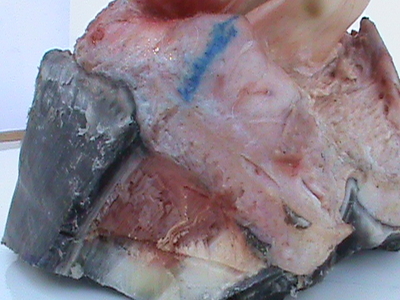

This photo shows clearly the dark gray outer hoof wall, the white inner hoof wall (water line) and the “white line” which is yellow and is the laminae (sometimes called the golden line).

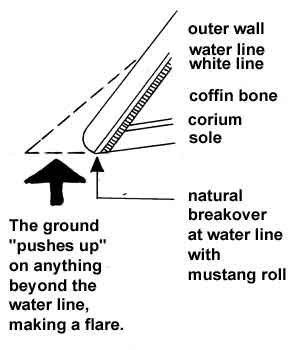

Why do we care about the water line? Because we often might rasp off all or most of the outer hoof wall right at the ground level, and the water line is a good indicator of where we usually should stop.

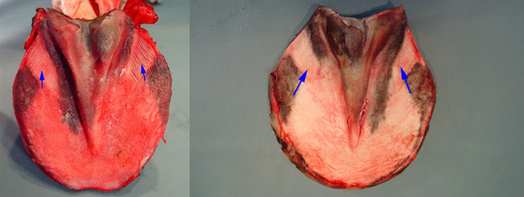

The white line is also important because it is one indicator of the health of the hoof. Because the white line is made up of the laminae, a stretched white line means there is something wrong. Here are two cases of stretched white line. See how the sole ends and there is space between that and the outer hoof wall.

Sometimes the sole will stretch right over the white line which means you can’t see stretching from the bottom of the hoof except for other indicators. A stretched white line will also show up as rubbery pieces that stick out around the edge of the sole.

People often ask me about this type of thing: Is this stretched white line?

Probably there is some based on the shape of this hoof and the long skinny frog, but just seeing lines on the outer hoof wall does not mean the line is stretched. There are laminae on the outer hoof wall and on the inner hoof, that connect together. So you might see those lines from the hoof wall laminae on any hoof that is left to overgrow for too long. I’ve often seen them and trimmed off the excess wall, only to find a tight white line still.

Another common question: Is this a stretched white line?

This is a tight white line. A healthy sole will form a ridge around the edge, between the hoof wall and sole. Sometimes this is called the dirt line. Seeing healthy yellowish laminae in that line is fine too.

Ideally you will see the sole growth reflecting the shape of a coffin bone, which is concave on the bottom but the sole also grows around the edge.

So the sole should be concave near the tip of the frog, but then rise up into a little hill around the edge that slopes down into the ridge/dirt line just inside the hoof wall (the illustrated hoof shows concavity but the outer hoof wall has been removed past the water line – this would be a type of correction trim, not a maintenance trim). The sole ridge/callus is only in the front half of the hoof, where the coffin bone is. The sole in the rear near the bars and behind is flatter.

The point of the frog is also often called the tip of the frog or the apex of the frog.

Our chart at the top of the page is missing the pillars of the hoof, which are another part of the hoof often talked about. On the hoof below, the pillars are marked in dark circles. They represent the forward weight bearing part of the hoof (research in wild horses showed that the weight bearing areas of the hoof are between the pillars and the heel of the hoof).

Something else often talked about is breakover. If the toes are too long/forward, breakover will be delayed. Sometimes this means the horse can’t get his front hoof out of the way in time to prevent the back hoof from striking it, or it may interfere with a natural stride.

When we talk about bringing breakover back, we mean that making the hoof less long from heel to toe helps the breakover happen earlier/faster. This is always beneficial to the horse.

Hopefully everyone knows what the sole is. It is meant to be concave around the tip of the frog. This hoof shows both concavity and the sole ridge around the edge of the sole. See how it makes a rim like the rim of a crater.

However, a hoof can be too concave, as in the hoof below. Many club hooves have too much concavity for health. This can also be seen in some hooves of gaited and show horses that are kept abnormally long.

Something else to notice is when a sole is healthy versus exfoliating versus bruised.

This is bruising.

This is a hoof with dark pigment (not bruising).

This is shedding or exfoliating sole. It is another situation often confused with white line stretching or disease. It is a natural process that happens when there is wet weather after a period of dry (horses often retain extra sole when it is dry/the ground is hard).

This is what a healthy frog looks like. It should be wide in the heels, and the central sulcus (depression in the center) should be open like a thumbprint.

This is what an unhealthy frog looks like. The central sulcus has narrowed to a crack and breeds infection.

Also unhealthy.

The seat of corn and collateral grooves are also important parts of the hoof anatomy. The collateral grooves can help give an indication of sole and bar depth and health.

The seat of corn helps show the correct angle of the bars and also getting the sole exfoliated in the seat of corn helps show where the heels need to be trimmed down to.

As a general rule, exfoliating/shedding sole is flaky or powdery and live sole is waxy. A caveat to this is that a hoof with contracted heels or a club hoof might have sole that has been compressed in the heels and it will remain waxy even after it is past the point of needing to shed out.

The heel buttress is the part of the hoof wall around the seat of corn that goes back to the widest part of the frog.

It is very important that the heel buttress is trimmed wide and flat to help with a heel first landing.

A horse with run forward heels has lost his heel buttress. Some people think of the heel buttress as a platform or landing zone. I try to think about if it looks like a horse can comfortably land on it after it’s been trimmed.

A horse with run forward heels has lost his heel buttress. Some people think of the heel buttress as a platform or landing zone. I try to think about if it looks like a horse can comfortably land on it after it’s been trimmed. It is important to know what the bars look like on the internal hoof so you know how they should grow.

It is important to know what the bars look like on the internal hoof so you know how they should grow.Here you can see the bar laminae – the bars grow at this angle from the heel buttress toward the frog.

If bars are left to grow long, they usually lay over. Abscesses can form from bruising related to trapped gravel, etc underneath long bars.

Trimmed, the bars will basically run along the collateral groove.

Some horses wear off the bars quite a bit so they don’t need much trimming. But it is good to keep an eye on them because they can cause problems. Bars can get pushed up inside the hoof, and this apparently happens more in club hooves and can prevent the horse from weighting the heel.

Heel bulbs are meant to be wide apart and big, not like this.

Hopefully you can see the difference.

All of that is the outside of the hoof. Now for the inside.

Something to note is that the coffin bone is also called the pedal bone, P3 and the third phalanx.

This is the network of blood vessels that supply the hoof.

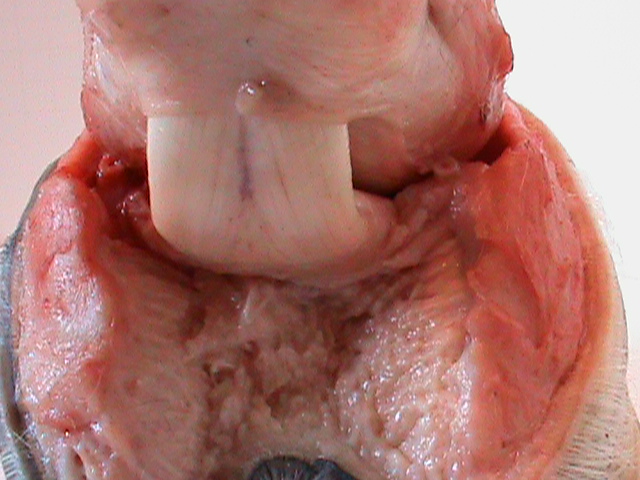

This is the rear of the hoof and the big white band is the deep digital flexor tendon. It runs underneath the navicular bone and connects to the underside of the coffin bone.

On either side of the hoof are the triangular shaped lateral cartilages. These flex apart as the pastern lowers toward the ground. A very tall hoof capsule will jam up over these and prevent some of the natural mobility and shock absorption. Between the lateral cartilages and underneath the deep digital flexor tendon is the digital cushion. It is made up of fibrocartilage.

The digital cushion has a type of cell that changes as a horse develops, from fatty connective tissue to dense fibrocartilage. What causes the cell to change is pressure. So a horse that has not had adequate exercise when young will have a digital cushion that is softer and has less of the dense fibrocartilage cells. Some development can happen later in life, but the horse loses the ability to change the digital cushion with age.

When you see how the deep digital flexor tendon runs under the navicular bone, you can see how many heel issues relate to soft tissue and/or bone damage from poor hoof angles.

*********************

The digital cushion provides lift at the back of the hoof. For many horses, the toe angle can only become so steep even when the coffin bone is sitting properly in the hoof, because the horse never developed a good digital cushion to provide the lifted angle at the heel of the hoof. This means that some horses will always tend toward having a low heel. This does not mean we need to let the heels get crushed under the hoof.

Here is another view of the deep digital flexor tendon, lateral cartilages and digital cushion. If a horse has too much pressure on the lateral cartilages from the hoof capsule being jammed up or too much hard work on concussive surfaces, the lateral cartilages can calcify. This is called “sidebone.”

Here is another view of the deep digital flexor tendon, lateral cartilages and digital cushion. If a horse has too much pressure on the lateral cartilages from the hoof capsule being jammed up or too much hard work on concussive surfaces, the lateral cartilages can calcify. This is called “sidebone.”

This photo shows how the internal foot sits on the sole in the hoof capsule.

Here are the laminae of the inner hoof, the sole corium (the tissue that the sole grows from) and you can see the bar laminae very well.

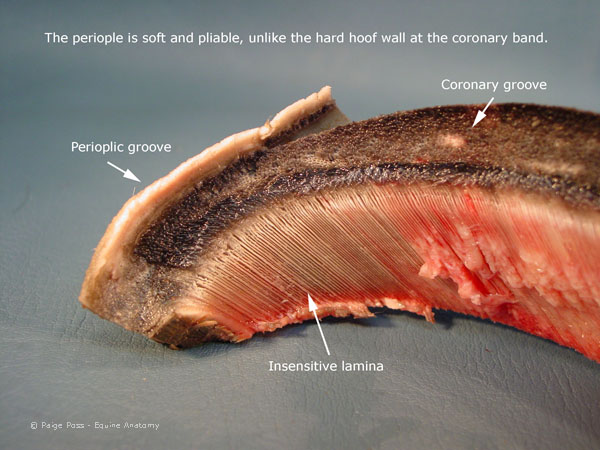

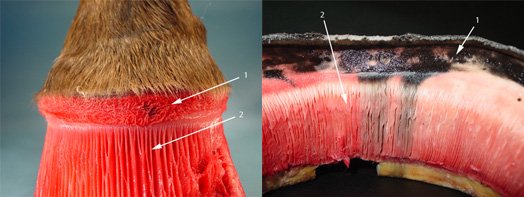

Here is a close up of the inside of the top of the hoof wall. Here you can see the laminae that are on the inside of the outer hoof wall, and how the hoof wall grows out of the coronary band.

The periople is similar to the cuticle of your nail. It often is visible on the outer top of the hoof and is most visible when the hoof is wet. Sometimes it grows quite a ways down the hoof.

Here is another view:

This shows the laminae of the inner and outer hoof wall. These connect together as the hoof grows down. Certain cells trigger the laminae to disconnect and reconnect with each other to allow the hoof to grow down and yet stay connected well enough to support a horse’s weight even with the force of movement. The laminae basically suspend the horse, as one brutal experiment showed back over a hundred years ago where they cut the soles off the hooves and the bones stayed in place. Some types of laminitis create a trigger where the laminae disconnect without reconnecting well.

Laminae that have been damaged grow back thicker and with forks/branches that are not normally present in undamaged laminae. A laminar wedge in the toe is made up of stretched laminae and/or the cells that are sent to repair damaged laminae. These cells build up into a hard/brittle substance that hold the hoof wall onto the hoof, but they don’t do as good of a job as healthy laminae.

Here you can see the inside of the hoof capsule. Everything here grows down from the internal hoof: the frog from the frog corium, the sole from the sole corium, the hoof wall from the coronary corium.

This is the internal hoof – what is inside the hoof capsule.

Another view showing the frog corium, sole corium and laminae.

The internal foot and hoof capsule next to each other. The internal hoof fits inside like a foot inside a shoe – except the shoe grows on the foot.

This picture shows where the soft/cartilage back part of the internal hoof meets the hard/bone front part of the internal hoof. It helps illustrate how the back of the hoof can get very distorted through abnormal growth. It is easily moved and compressed by the hard parts of the hoof.

Here you can see the size of the coffin bone compared to the size of the internal hoof.

Rear view of the outer hoof capsule.

Here you can see how the internal foot fits inside the hoof capsule.

This video is a great example of how the barefoot hoof orients itself with the ground before landing.

Barefoot hooves in slow motion:

An extra if anyone is interested:

Founding and timeline of barefoot hoof movement